In Asheville, North Carolina, vegetable farmers Becca Nestler and Steven Beltram are stuck between the impending spring season and the trickle-down effects of the government shutdown. Last week, when I spoke with Nestler — my friend since college — I asked about the farm. “We’re just stuck,” she told me. “We can’t even talk to our loan officer.”

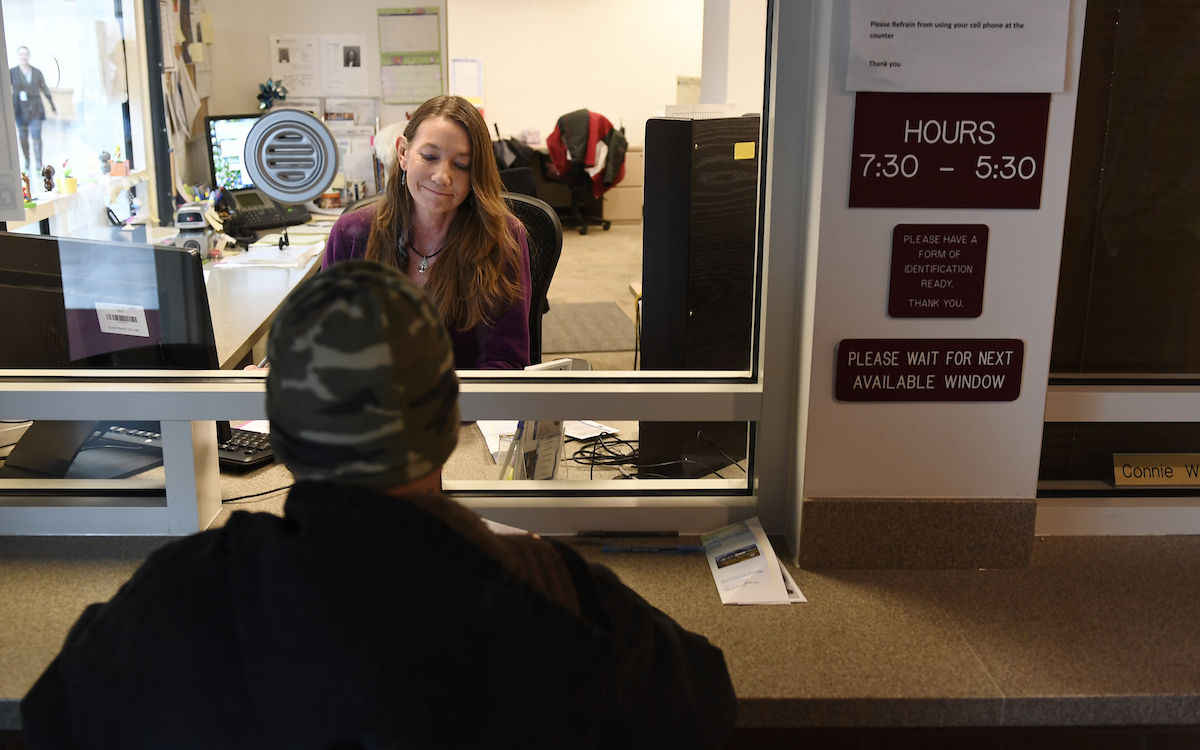

The longest government shutdown in history has rendered many federal agricultural services unavailable, including the thousands of Farm Service Agency (FSA) offices that assist farmers with dozens of programs, such as disaster relief and annual farm operating loans. This is the time of year when Nestler and Beltram should be working with their FSA officer to prepare their annual loan packet — but with the office closed and their officer furloughed (and prohibited from using work cell phones or email to respond to farmers), they’ve had no choice but to wait.

“Usually by now we’re far enough down the road that we know the loan is going to get processed,” said Beltram. “But right now, we don’t have those assurances, because we haven’t been able to communicate with [the FSA].” With spring just around the corner, every week counts. Last year, they applied for their loan on Jan. 1 and received their funds five weeks later, on Feb. 6.

Get Talk Poverty In Your Inbox

Last week, some FSA offices re-opened for a three-day period to work solely on existing loans and 1099 tax form preparation for borrowers, as those forms are due on Jan. 31. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue also announced that FSA offices would reopen on Jan. 24 for two weeks, and would offer “a longer list of transactions” for farmers, including operating loans. At the end of two weeks, if the government has still not reopened, FSA offices will move to a three-day work week schedule. All FSA employees will work without pay until the government re-opens.

Even with these measures, and even if the government does re-open soon, the damage has already been done. “I mean, if I’m reading the tea leaves, the best case scenario is they’re going to show up on the 24th with a huge backlog of stuff to do … and we’re not going to get our loan near on time,” said Beltram.

In fiscal year 2018, the USDA loaned a total of $5.4 billion, which helped farmers buy property, equipment, and necessary inputs, such as seeds and fertilizer — all of which are vital to farm operations and also prop up small rural economies.

Take tomatoes. At the beginning of February, Beltram and Nestler order seedlings from a local greenhouse, which requires a 50 percent deposit. By mid-March, they’ll begin fertilizing and prepping their fields, and seedlings will be transplanted in mid-May. They’ll spend money on inputs — fertilizer, irrigation and field supplies, fuel for their vehicles, shipping boxes, and labor — for tomato plants that won’t mature to generate revenue until mid-August. That’s at least six months without cash from sales.

“So every spring, we go to our lender, which is the FSA, and they loan us operating funds to put our crop in the ground,” said Beltram. “It’s the way farming has always been. … If you weren’t working with the bank 100 years ago, you were going to the general store and buying everything on credit until your crops came in.”

Factoring in costs for their entire 60-acre farm (which also includes organic leafy greens), Beltram estimates they’ll need $200,000 just in establishment costs, before they even think about harvest.

As they purchase their supplies and pay their employees, those funds naturally ripple out to others in the community. But the shutdown has brought this seasonal farm economy to a halt, freezing out farm families and small businesses already on the brink.

– Steven Beltram

The shutdown situation also exacerbates a rough few years in farm country. In November, the USDA projected that net farm income would decline by $10.8 billion (14.1 percent) in 2018 — just 3.3 percent above the 2016 level, which was the lowest since 2002. As a result, the United States is losing farms in an eerie echo of the 1980s farm crisis, an economic disaster that upended rural America. In Wisconsin alone, 638 dairy farms closed up shop in 2018. Adding to the problems, President Donald Trump’s trade war made pawns out of commodity farmers, resulting in retaliatory tariffs that had sweeping and disastrous effects.

“Had [President Trump] set out to ruin America’s small farmers, he could hardly have come up with a more effective, potentially ruinous one-two combination punch than tariffs and the shutdown,” wrote Iowa radio news director Robert Leonard in a New York Times op-ed.

Climate change brought extreme weather to farm country as well. In North Carolina, Hurricane Florence was estimated to cost farmers more than $1 billion in damage and loss. And over the course of the season, Nestler and Beltram received more than 100 inches of rain (Asheville’s annual average is 45 inches), which caused massive flooding and wiped out 30 percent of their entire crop.

“It was the worst year we’ve ever had at the farm, financially,” said Beltram. “I don’t know any farmers in this area that have money sitting around right now. Everybody I know either broke even or lost money this year.” And then came the shutdown: He knows farmers who can’t pay their rent, buy groceries, or pay for day care because of the effect the government’s closure has had on their finances.

Beltram and Nestler plan to head to the FSA office as soon as it re-opens, but don’t expect to get their loan funds until mid-March, at best. In the meantime, they’ll go to the bank to apply for a bridge loan, and are considering the possibility of cash advances from credit cards until their FSA loan can be processed.

“I’ve been farming long enough that I can’t sweat things too much. I just have to have faith that it’s all going to work out,” Beltram said. “But there’s no question that our livelihood is seriously threatened by what’s going on.”