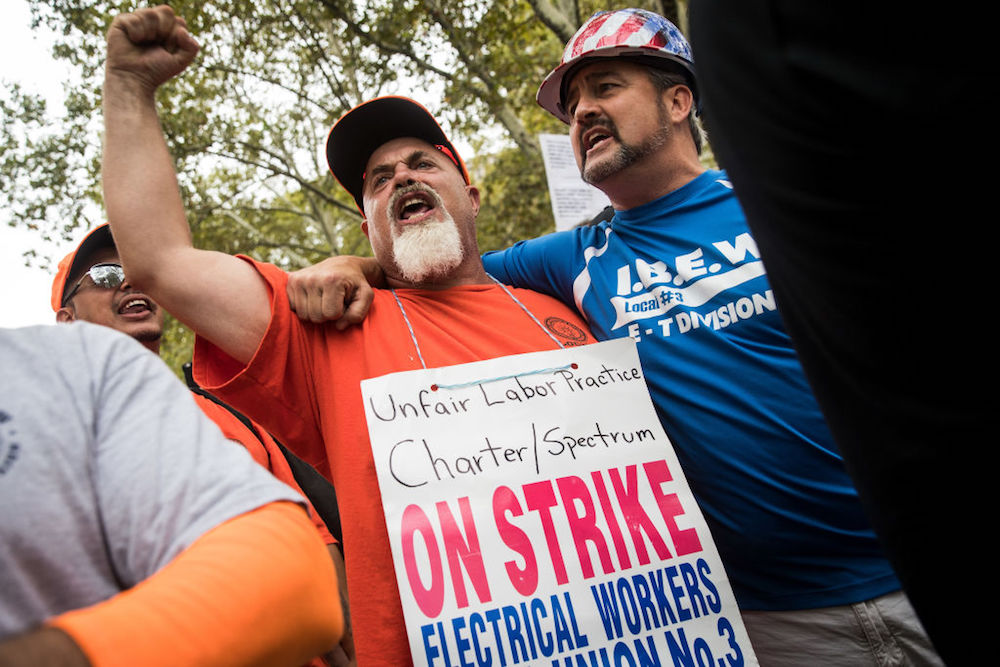

Like many of the 1,800 New York City cable technicians who walked off the job after negotiations with Charter Communication — which operates as Spectrum Cable — broke down in March 2017, David Papon, a plant engineer, assumed the strike wouldn’t last too long. As a 27-year veteran of the company, with a wife and four children to provide for, he was uneasy about being out of work for an extended period of time but felt like the company left the union little choice.

After acquiring TimeWarner Cable in 2016, Spectrum began an attempt to replace its union health insurance and pension plans with a company-run 401(k) pension account and health plan. The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 3 objected to the plan as “substandard,” preferring to hold on to its existing pension plan, which for decades has been run by an independent board of trustees. Union officials feared that if they gave Spectrum control of their pension fund and health care, they would forfeit any leverage they had in future negotiations. With families to support, workers like Papon couldn’t afford to lose everything they worked so hard for.

Get Talk Poverty In Your Inbox

“The strike caught everyone by surprise but my main concern at the time was maintaining our medical and our pension. That was our main goal and something that Spectrum definitely wanted to eliminate. If they wanted to take that away, we had no other choice but to go on strike.”

What Papon and his fellow IBEW Local 3 members couldn’t anticipate was that more than three years later, they would be part of one of the longest strikes in American history. As the strike dragged on, developing into a bitter war of attrition between Charter Communications — which is the largest provider of cable TV, internet, and telephone service in New York State as well as the second-largest cable provider in the country — and Local 3, workers like Papon struggled to make ends meet.

To make up for his lost income, Papon took a job on construction sites, starting at the bottom of the trade union ladder. Despite taking another job, things didn’t become easier. He fought his bank’s attempt to foreclose on his home and his wife and daughter were diagnosed with lupus. His wife became so ill that she is currently awaiting a lung transplant. With legal and medical bills piling up, he quickly saw his life savings evaporate.

“I had to deplete my 401k completely in order to survive and to maintain my family,” said Papon. “That hurts. After so many years you have built this savings and this cushion so you could be able to retire later on. Now all of sudden you have this money gone which is pretty sad. Definitely it has affected me mentally.”

As if being on strike hasn’t been hard enough, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced Papon’s family deeper into crisis. With all non-essential construction suspended, Papon has found himself unemployed and without health insurance for the first time in his life.

“With the COVID, my wife and daughter can’t afford to get sick because they don’t have an immune system. So I’m really unsure on what to do.”

Papon is not alone. Troy Walcott, a 20-year Spectrum veteran and a union shop steward, has been one of the strike’s most visible leaders. With many striking workers moving on, Walcott has been desperately attempting to keep the strike’s momentum alive. But amidst a full-blown pandemic, it has felt like an arduous battle.

“Whatever people are going through before the pandemic, now times are harder for them. So it has been like that for us for basically three years. We have scraped by, barely having enough to hold on to keep going, at the bottom of the barrel, but now we get kicked in the teeth again through this pandemic.”

For his part, Walcott was forced to drive for Uber to sustain himself. Yet, without any health insurance, he can’t afford to put his life on the line and continue driving.

“Between working for Uber and pulling from my savings that has been enough to get by. Now with the pandemic it’s all savings. I know eventually it gets to the point where the balance I’m in will fall through. I’m playing on borrowed time and I can’t really do anything except keep fighting and hoping we get help from somewhere.”

Supporters of the striking workers, such as New York City Council Member Barry S. Grodenchik, are dumbfounded that, after three years, Spectrum has still refused to reach an agreement with Local 3 over their pension fund and healthcare plan, even during the COVID-19 crisis.

“I grew up across the street from the union hall, so I go way back with the union and many of the people that are unfortunately caught up with this,” said Grodenchik. “It’s very, very hard to see this at this time, especially during the pandemic. They have been trying to sustain a strike for over a three-year period of time which is quite unusual to say the least.”

Instead of negotiating with Local 3, Spectrum has hired an army of contract workers to replace the striking workers and has launched a bid to decertify the union. Voting for decertification should be led by workers who choose to either abolish a union or replace it with a different one. Local 3 contends that the vote is being pushed by replacement workers at the behest of Spectrum. In 2019, Local 3 lodged a complaint against Spectrum with the National Labor Relations Board, currently stacked with anti-labor Trump appointees, for unfair labor practices. The case has yet to be resolved. As of publication, Spectrum could not be reached for comment.

Congress, however, has signaled some support for organized labor. This past February, the House passed the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, one of the strongest pieces of labor legislation passed in years. The act would strengthen workers’ ability to form unions by introducing penalties against businesses that block workers from forming unions. It would also require companies like Spectrum to bargain in good faith with unions as well as protect workers’ rights to strike. Unfortunately, the act is unlikely to pass in the Repulican controlled Senate.

At the local level, many New York City officials are vowing to revoke Spectrum’s municipal franchise agreement with the city, which is up for renewal in July, if the company fails to reach a settlement with the union. The agreement gives Spectrum the privilege to provide cable, internet, and other tech services to residents across the city for a fee. Across the country, cable operators pay nearly $3 billion annually in franchise fees to state and local governments. Barry Grodenchik, who sits on the New York City Council’s Subcommittee on Zoning and Franchises, has been one of the most vocal in his opposition to Spectrum.

“I stated publicly that I cannot vote to extend their franchise agreement because of how they treat their workers. There are 1,800 families in New York City that have been shown the door. That’s a lot of people.”

Even New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio has signaled his support for the striking workers. “Workers deserve a fair contract, and this Administration strongly supports the striking workers,” said Laura Feyer, Deputy Press Secretary for the Mayor. “Like all cable franchise agreements, Spectrum’s is governed by federal law, which has strict guidelines regarding when a franchise can and cannot be renewed.”

Yet, some of the strikers are skeptical. “Many elected officials have stated that they will not vote to renew Spectrum’s franchise agreement, which has to be done as a stance against a company that is blatantly union busting in a union town,” says Walcott. “But the problem is, even after the vote, the cable company is going to lawyer up and just going to fight the city for years without a franchise agreement. So they don’t really give a shit.”

For David Papon, with all his struggles, he has lost what little faith he had in the company. “After all the years I put into the company I feel abandoned. This company pretty much has nobody’s back. It’s a money company and we are just a number to them.”