Camden, located in the southern part of New Jersey, just across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, is one of the poorest cities in the state, if not the whole U.S. The median income there is just $26,000, compared to $76,000 in the rest of New Jersey, and the poverty rate is above 37 percent. In the 2013-2017 period, per capita income in Camden was just $14,405.

But income isn’t the only issue: Camden is also infamous for being a “food desert.” According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, huge swathes of the city are populated by people who live in low-income neighborhoods, don’t have a car, and don’t have a grocery store within half a mile of their homes.

New Jersey lawmakers have been trying to “help” Camden for what feels like forever, and one of their ideas was to use tax incentives to entice new grocery stores into the city. But instead of bringing in new shopping options and addressing entrenched inequality, the effort showed how giving tax breaks to private corporations doesn’t help local economies or reduce poverty.

Get Talk Poverty In Your Inbox

First, some background. At the behest of Gov. Phil Murphy (D), a task force is looking into New Jersey’s corporate tax incentive programs, which, in theory, use tax breaks to entice and retain businesses, thus creating jobs and boosting incomes. What the task force has found so far is that those programs are a total mess: Instead of creating good jobs for residents of the state, they’ve allowed connected lawyers and lobbyists to direct tax breaks to their clients, who often broke their job creation promises, all at an exorbitant cost to taxpayers.

Case in point: The effort to bring a grocery store to Camden. In its first official report, the task force noted that a provision of a 2013 rewrite of New Jersey’s corporate tax incentive programs specifically addressed grocery stores in Camden, under a program called Grow NJ. But a politically connected law firm called Parker McCay — whose CEO happens to be the brother of a prominent New Jersey Democrat — “drafted large swaths of the [tax incentive] bill in various respects that appear to have been intended to benefit the firm’s clients,” according to the task force. That included shaping the grocery store provision to explicitly help its client, ShopRite, and prevent other grocery stores from benefiting from the tax break.

Here’s what the law firm allegedly did: It represented a joint project to have a ShopRite anchor a larger retail area in Camden, which was announced before the state legislature rewrote New Jersey’s tax incentive programs. That project, per the task force “was planned to be over 150,000 square feet, with at least 50 percent occupied by the grocery store.” Another developer was, at the same time, pushing a smaller project that also included a grocery store.

When New Jersey’s new tax incentive programs were later announced, the criteria for grocery stores were very specific. Grocers only qualified if they were “at least 50 percent” of a larger retail development “of at least 150,000 square feet” — the exact specifications that ShopRite had planned. (At the time, the average grocery store in the U.S. was 46,000 square feet.) As a result, the incentive explicitly helped ShopRite and rendered its competitor ineligible for the tax break, even though either project would also have fulfilled the goal of opening a supermarket in an underserved area.

Ultimately, ShopRite didn’t follow through on its Camden project, and neither did the second store that was made ineligible for subsidies. So the end result was no new grocery store in Camden at all. Instead, a sealant company took the site ShopRite would have used, thanks to $40 million in tax breaks; per the Philadelphia Inquirer, “No explanation has been provided for why the ShopRite project collapsed.” (In 2014, a PriceRite opened in Camden that was also too small to qualify for the tax breaks ShopRite would have enjoyed.)

Camden’s grocery stores were one of many examples in New Jersey’s incentive programs in which private concerns trumped the public interest. As the task force put it in its report: “Certain aspects of the Grow NJ program’s design are difficult to justify from a rational policy perspective and can be understood only as the result of a process in which certain favored private parties were permitted to shape the legislation to their benefit — and further, in some cases, to disfavor potential competitors.”

Sadly, such inside wheeling and dealing is a standard part of corporate tax deals. In fact, according to a study by the Kansas City Federal Reserve, an increase in a state using corporate tax incentives is correlated with an increase in its officials being convicted of federal corruption crimes. That connection makes a certain sort of sense, since corporate tax incentives are targeted to specific industries, if not specific companies, making a coziness between elected officials and corporate interests nearly inevitable.

But inside dealing aside, was using tax breaks to entice grocery stores into Camden even a promising strategy? A growing body of research says probably not.

One problem inherent in tax incentives is that they often go toward “incentivizing” actions that the business receiving them would have taken anyway, for other reasons. A study by Timothy Bartik at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research found that at least 75 percent of incentives wind up merely being free money for companies that planned to take such action regardless of the incentive. That’s also true with grocery stores: A 2017 study found that up to about 70 percent of grocery stores that entered low-income areas due to the federal New Market Tax Credit likely would have done so even in the absence of the credit.

There’s also plenty of evidence that bringing grocery stores into food deserts isn’t necessarily the panacea for those areas that advocates claim it is. Higher-income and lower-income households actually spend about the same amount of money on average in supermarkets: 91 cents of every dollar spent on groceries versus 87 cents, respectively. They also travel roughly the same distance to those stores, on average.

So simply bringing a store into the neighborhood cuts down on travel costs, but doesn’t have all the ancillary benefits — better diets and better health — that policymakers claim will occur. Diet is much more closely connected to the amount of money a household has and in what region of the country it’s located.

“The primary factors are economic and time constraints that are affecting people, not geographic barriers, in wealthy countries,” said University of Iowa College of Law Adjunct Professor Nathan Rosenberg. “The more studies that have been done, the stronger those studies are, and the better the data we have, the more clear that’s become.”

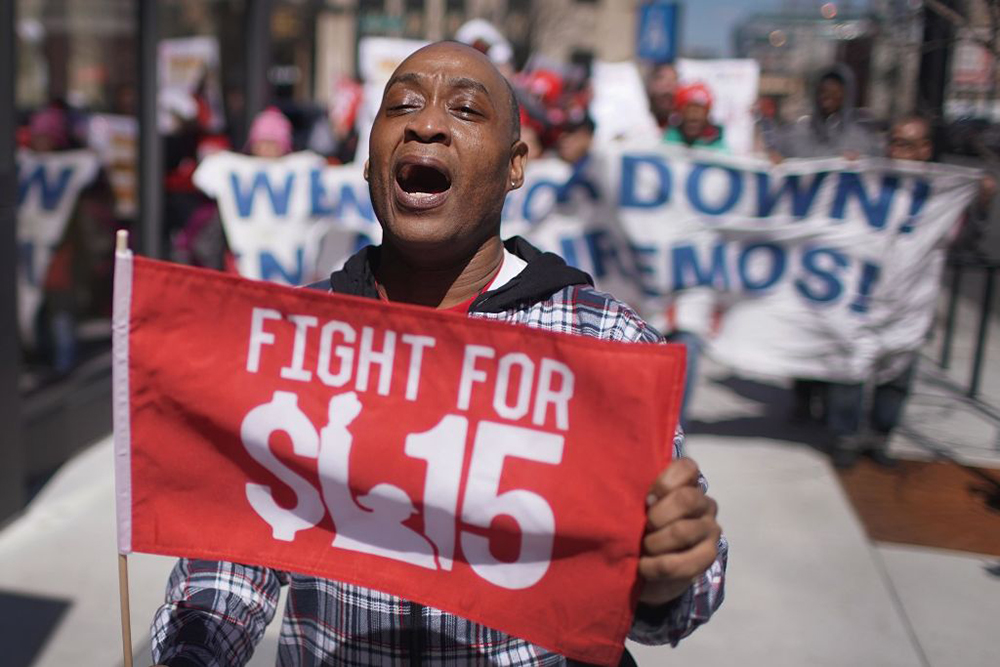

In 2018, Rosenberg argued in a paper he co-wrote with Nevin Cohen entitled “Let Them Eat Kale” that incentives for grocery stores get the food access solution precisely backward. Instead, Rosenberg and Cohen noted that boosting wages, strengthening worker protections, and increasing funds for programs such as those providing school lunches will all do more to address the root causes of food-related inequality.

So New Jersey lawmakers took a dubious idea, made it worse by allowing politically connected players to influence the process, and wound up achieving nothing for the people of Camden. Sadly, that’s often how programs like Grow NJ shake out: Good for the rich and connected, and leaving everyone else hungry for better solutions.