In March, three Michigan cities began cracking down on pedestrian violations. The stated goal of the week-long effort was to reduce the significantly high pedestrian traffic casualties in those municipalities by getting pedestrians to obey traffic laws. In at least two of the targeted Michigan cities, jaywalking tickets run more than $100 apiece.

But targeting walkers doesn’t do anything to address the actual problem: that roads and sidewalks aren’t safe and accessible for all users. Instead, what this enforcement does is punish vulnerable people, contribute to an already-existing social mentality that blames pedestrians for their own demises, and send a clear message that safe streets are only a priority for people who drive.

According to the Detroit Free Press, Kalamazoo, Detroit, and Warren, the Michigan cities that participated in the pedestrian enforcement campaign, targeted jaywalkers — in particular, those who failed to cross streets at an intersection, who failed to follow traffic signals, who didn’t walk on the sidewalk, who didn’t walk facing traffic when on a roadway, and who didn’t yield to vehicle traffic with the right of way.

In order for traffic to flow smoothly and for people to stay safe, it is reasonable to expect everyone to follow the rules of the road. But when the road isn’t made for you, those rules can be tricky to follow, and in fact, even when they are followed to a T, walkers and bikers are no match for a two-ton vehicle whose driver is unaware of how to share the road with pedestrians — or simply doesn’t care.

Get Talk Poverty In Your Inbox

From 2008-2017, according to a report from the Governor’s Highway Safety Association, pedestrian deaths increased by 35 percent. In 2018, the report estimated that there were 6,227 pedestrian fatalities in the U.S. — the highest number since 1990.

When bicyclists are included, those figures are even higher. And unlike motor vehicle fatalities, which are declining, pedestrian and bicycle fatalities are increasing.

The report cites things such as population growth and the shift in vehicle-buying from passenger cars to SUV’s as major factors that contribute to pedestrian fatalities. As city populations grow and as pedestrian commuters increase, car-centric street designs are increasingly dangerous.

Enforcing fines on pedestrians doesn’t fix these issues, it just sends an overt message that streets aren’t for pedestrians; they’re solely for people who drive. Meanwhile, it’s low-income people who are least likely to own a car and to have to walk on unsafe roads.

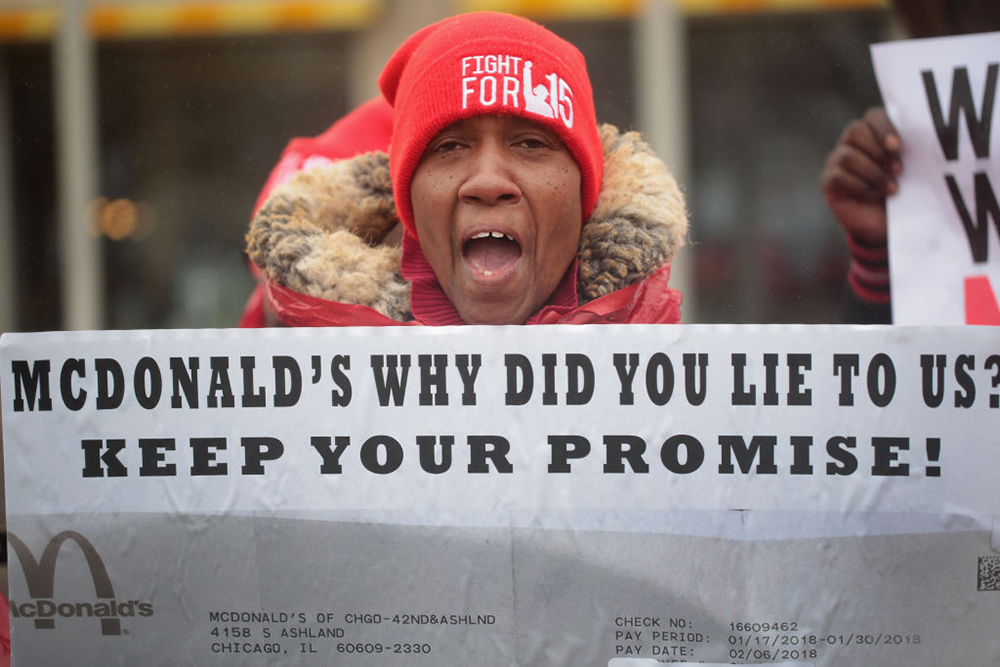

In addition, in communities that have targeted pedestrians with citations, trends have shown that marginalized people are the most impacted. For instance, in December of 2017, ProPublica reported that in Jacksonville, Florida, black pedestrians were disproportionately targeted with pedestrian tickets. Not only did black pedestrians there receive more tickets (55 percent of tickets went to black people even though they make up only 29 percent of the city’s population), they also were most affected by driver’s license suspension for failure to pay those tickets. A similar trend was noted in Seattle.

But there are alternatives, such as developing Complete Streets policies, which are designed to make streets safe for all users, including pedestrians, bicyclists, car drivers, and transit riders of all abilities. The model focuses on reducing pedestrian risk by placing physical barriers between cars and pedestrians, redesigning intersections and sidewalks, and modifying traffic flow. More than 1,400 Complete Streets policies have been passed in the United States. That figure includes 33 states that have adopted some form of a statewide policy.

However, that doesn’t mean those communities and states have full and adequate protections for pedestrians and bicyclists. A Complete Streets Atlas shows large swaths of the U.S. without any Complete Streets model at all, and of those that have adopted some policies, most do not have full bike and walking path protections.

Redesigning streets to accommodate all users requires traffic studies, planning, and redesigning, all of which come at a cost. But when cities are grappling with high rates of pedestrian casualties, they should invest time and money in that crisis. The Michigan cities that participated in the week-long enforcement period targeting pedestrians were each awarded grants to cover overtime for their police officers. Instead of investing in addressing the structures that lead to pedestrian casualties, they took the short-term, punitive approach — an investment that could never produce the kinds of benefits that structural changes to road design could.

In the mid-1980s, Florida adopted a statute requiring that roadway design accommodate walkers and bicyclists from the beginning. A study published in the American Journal of Public Health estimated that in the three decades following, more than 3,500 lives were saved as a result, with pedestrian lives among the most likely to be saved.

Other cities have not only implemented ordinances that protect pedestrians; they center their enforcement of those ordinances on drivers. In Ann Arbor, Michigan, for instance, an ordinance requires drivers to stop for a pedestrian approaching a crosswalk. This is more stringent than the state requirement that a driver stop for a pedestrian in a crosswalk. The city did targeted enforcement of the ordinance between 2017 and 2018, and during that time police issued more than 800 tickets to motorists who violated the city’s pedestrian law.

As much as our culture loves to blame the victims, pedestrians aren’t responsible for their own demise. Still, following each pedestrian accident, the comment stream centers blame on the victim. “Why were they crossing there?” “Were they wearing bright vests?” Instead of focusing on the structural problem of roads with increasingly heavy and fast-moving traffic or the lack of safe pedestrian paths, the culture at large points fingers at the road users who are most in danger. Ticketing pedestrians reinforces this norm.

But punishing pedestrians won’t change the stark reality that walkers, wheelchair users, and bikers must navigate spaces that weren’t designed for them to maneuver safely. Municipalities must grapple with this safety crisis and recognize that punishing those who are most in danger while using the road isn’t the answer; safer streets are.