With a majority of Americans now concerned about wealth and income inequality in our country, TalkPoverty is launching a new feature, “10 Solutions to Fight Economic Inequality.” We asked experts to use this list by economist Tim Smeeding as a sample and to offer their ideas on how to dramatically reduce poverty and inequality in America. We hope you will use these lists as a resource to educate yourself and others, and that you will return here in the weeks and months ahead as we update this post with more lists from more contributors. As always, we welcome your ideas in the comments below. Anything particularly resonate? Anything missing?

Thanks for reading and sharing.

Jared Bernstein’s Top 10 to Address Economic Inequality

Olivia Golden: Policies to Reduce Income Inequality

Kali Grant and Indivar Dutta-Gupta: Ten Ways to Fight Income Inequality

Erica Williams: What States Can Do to Address Inequality

Valerie Wilson: Top 10 Ways to Address Income Inequality

Jared Bernstein’s Top 10 to Address Economic Inequality

(Author’s note: many of these ideas fall under the heading of achieving full-employment in the job market, such that the matchup between the number of jobs and job-seekers is very tight. This is an essential intervention for both real wage stagnation and inequality.)

- If the private market fails to provide enough jobs to achieve full employment, the government must become the employer of last resort.

- When growth is below capacity and the job market is slack, apply fiscal and monetary policies aggressively to achieve full employment. Right now, this means not raising interest rates pre-emptively at the Fed and investing in public infrastructure.

- Take actions against countries that manage their currencies to subsidize their exports to us and tax our exports to them. Such actions can include revoking trade privileges, allowing for reciprocal currency interventions, and levying duties on subsidized goods.

- Support sectoral training, apprenticeships, and earn-while-you-learn programs.

- Implement universal pre-K, with subsidies that phase out as incomes rise.

- Raise the minimum wage to $12/hour by 2020 and raise the overtime salary threshold (beneath which all workers get overtime pay) from $455/week to $970/week and index it to inflation.

- Provide better oversight of financial markets: mandate adequate capital buffers, enforce a strong Volcker Rule against proprietary trading in FDIC-insured banks, strengthen the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and encourage vigilant oversight of systemic risk in the banking system by the Federal Reserve.

- Level the playing field for union elections to bolster collective bargaining while avoiding, at the state-level, anti-union, so-called “right-to-work” laws.

- Maintain and strengthen safety net programs like the EITC and CTC, SNAP, and Medicaid.

- In order to generate needed revenue and boost tax fairness: reduce the rate at which high-income taxpayers can take tax deductions, impose a small tax of financial market transactions, increase IRS funding to close the “tax gap” (the difference between what’s owed and what’s paid), and repeal “step-up basis” (a tax break for wealthy inheritors).

Get TalkPoverty In Your Inbox

Melissa Boteach and Rebecca Vallas: Top 10 Policy Solutions for Tackling Income Inequality and Reducing Poverty in America

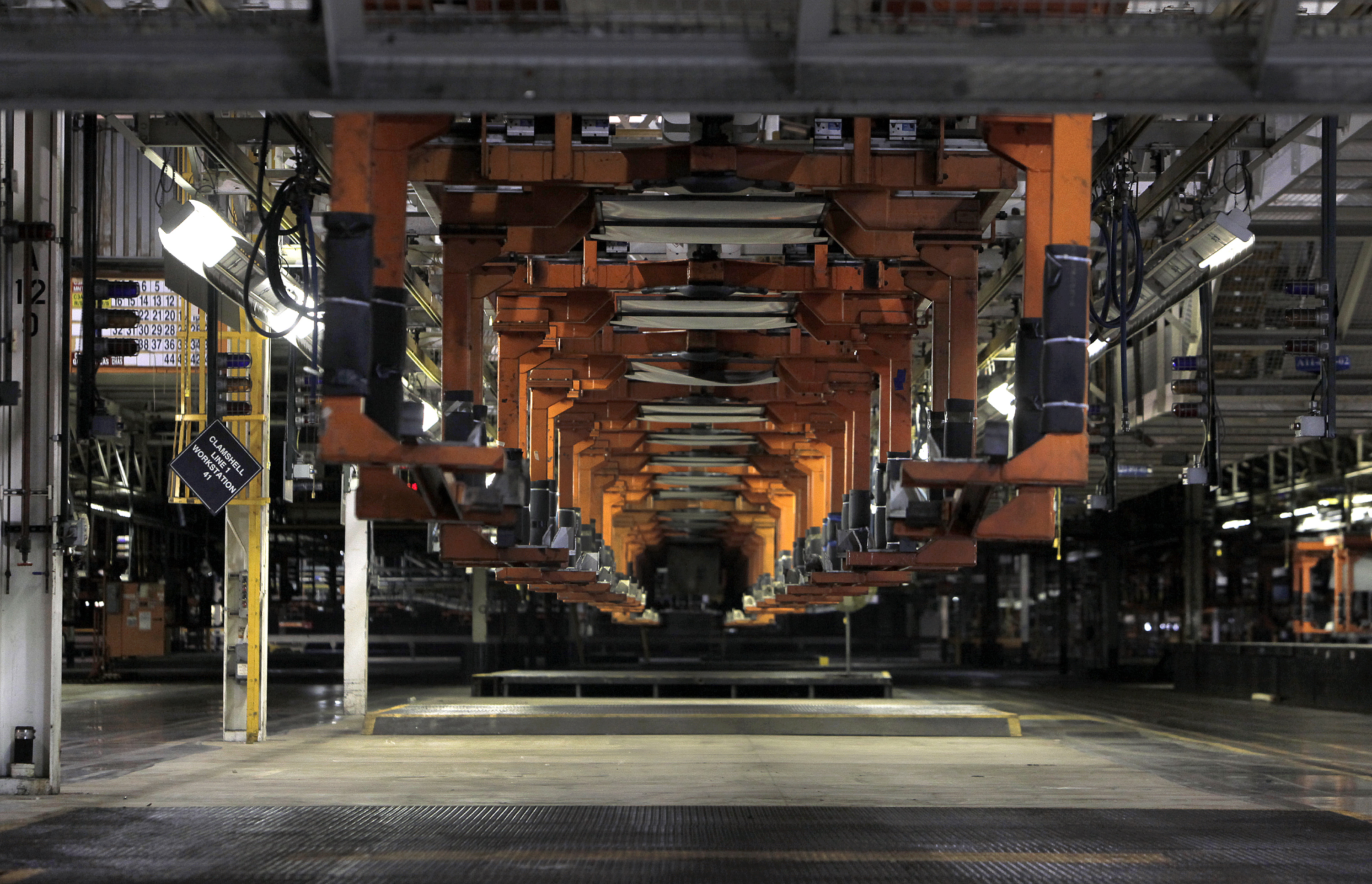

- Create jobs by investing in infrastructure, developing renewable energy sources, renovating abandoned housing and significantly increasing affordable housing investments, and making other commonsense investments to revitalize neighborhoods.

- Improve job quality and strengthen families by raising the minimum wage to $12/hour by 2020; ensuring pay equity by passing the Paycheck Fairness Act; strengthening collective bargaining; and enacting basic labor standards such as fairer overtime rules, paid sick and family leave, and right to request flexible and predictable schedules.

- Make the tax code work better for low-wage working families by making permanent the 2009 Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit improvements and expanding the EITC for childless workers and noncustodial parents.

- Invest in human capital by expanding access to high-quality and affordable childcare and early education; creating pathways to good jobs such as apprenticeships, national service opportunities, and a national subsidized jobs program; and implementing College for All to ensure that any student attending public college or university does not need to pay any tuition and fees during enrollment.

- Ensure that workers with disabilities have a fair shot at employment and economic security.

- Reform the criminal justice system to end mass incarceration and remove barriers to economic security and mobility for the one in three Americans with criminal records.

- Enact comprehensive immigration reform that provides a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants.

- Expand Medicaid and ensure that all Americans can access high-quality, affordable health coverage.

- Close tax loopholes that benefit the wealthy and special interests and raise taxes on capital income.

- Protect and strengthen investments in basic living standards such as nutrition, health, and income insurance. This includes reforming counterproductive asset limits, and ensuring that programs such as unemployment insurance are there for more workers if they lose their job.

Olivia Golden: Policies to Reduce Income Inequality

- Make work pay for all workers, including childless adults, by raising the minimum wage and strengthening the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit.

- Ensure stability for workers and their families through access to paid leave and predictable job schedules. Pass federal bills such as the FAMILY Act, Schedules That Work Act, and Healthy Families Act that mirror strong state and local laws.

- Identify and tear down the systemic barriers that people face because of race, ethnicity, language, and immigration status, for example by making college prep courses equally available in high schools attended mostly by students of color or by providing work authorization and a path to citizenship for immigrant parents.

- Ensure that every working family can afford high-quality child care through significant investments in the Child Care and Development Block Grant, Head Start and Early Head Start, and preschool for all three- and four-year-olds.

- Give children and their parents a simultaneous boost through two-generational policies and investments, including home visiting, support for parental mental health, and support for parents’ career development coupled with high-quality early care and education for children.

- Help low-income youth and adults access employment and training opportunities that lead to economic success by fully funding the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) as well as subsidized and summer jobs programs.

- Fully fund Pell Grants to help low-income students access higher education and develop the skills needed to compete in a competitive job market.

- Ensure that everyone, including low-wage working families and single adults, has access to basic health and nutrition by expanding Medicaid in every state and increasing SNAP benefits.

- Strengthen capacity of states to employ more streamlined and integrated approaches to delivering key public work supports (such as health coverage, nutrition benefits, and child care subsidies) so low-income working families can stabilize their lives and advance their career

- Rebuild unemployment insurance and cash assistance to ensure a strong safety net that supports poor and low-income children, families, and individuals when they need it.

Kali Grant and Indivar Dutta-Gupta: Ten Ways to Fight Income Inequality

- Correct political imbalances—strengthen and protect the Voting Rights Act, level the playing field for political contributions, and limit the influence of corporate lobbyists.

- Ensure that the wealthiest people and profitable corporations that benefit the most from our political and economic system contribute their fair share: reform “upside-down” tax expenditures (spending through the tax code that disproportionately benefits those with higher incomes), limit corporate welfare, and enact a robust inheritance tax.

- Amplify workers’ bargaining power by increasing fines for illegal anti-union behavior, encouraging minority unions, and reversing state laws that undermine unions and prevent them from collecting dues for benefits they provide workers at unionized workplaces.

- Update labor standards—raise the national minimum wage to $12 and index it to wage growth, require fair scheduling for workers, target employee-contractor misclassification and wage theft, and enact the Paycheck Fairness Act.

- Modernize the safety net—update Unemployment Insurance to reflect the changing nature of work; increase Social Security benefits and raise the cap on income subject to taxes; expand Medicaid in every state; and address flaws in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) to refocus it on employment and child well-being outcomes.

- Provide families tools to manage their many responsibilities—provide at least 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave, universal early learning and care, an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a child allowance, and comprehensive family planning services.

- Expand opportunities for current and future workers—invest in infrastructure and other nationally needed jobs; enact income-based loan repayment to increase higher education accessibility and affordability; and pursue full employment.

- Increase affordable housing and bolster consumer financial protection rules—promote fair and accessible banking, savings, and other financial vehicles and services for those excluded or abused by the current system.

- Attack racial and other discrimination across the board and enact comprehensive immigration reform, normalizing the status of more children and workers to increase their educational and work opportunities.

- Reduce the over-incarceration and over-criminalization by every level of government that restricts millions of Americans’ ability to support themselves and their families—especially among communities of color and high poverty areas.

Erica Williams: What States Can Do to Address Inequality

- Make state tax systems less regressive. State tax systems tend to ask the most from those with the least because they rely heavily on sales taxes and user fees, which hit low-income households especially hard. States can move their tax systems in a more progressive direction by strengthening their income taxes, adopting state earned income tax credits (or other low-income tax credits) to boost after-tax incomes at the bottom, and rejecting tax cuts that disproportionately benefit higher-income families and profitable corporations.

- Expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

- Raise the minimum wage and index it to inflation. States can raise wages for workers at the bottom of the pay scale by enacting a higher state minimum wage and indexing it so that it keeps up with rising living costs.

- Protect workers’ rights. States can raise wages by protecting workers’ right to bargain collectively and by strengthening and enforcing laws and regulations to prevent abusive employer practices that deprive workers of wages they are legally owed.

- Improve unemployment insurance.Unemployment Insurance helps workers who lose their jobs through no fault of their own to avoid falling into poverty and to stay connected to the labor market. States that have cut benefits should restore those cuts; others should build on recent efforts to fix outmoded rules that bar many workers from accessing benefits.

- Establish subsidized employment programs for low-income parents and youth that provide temporary jobs of last resort (mostly in the private sector), such as those many states created in 2009 and 2010 through the TANF block grant. These programs proved popular with participating businesses, families, and state officials of both parties.

- Improve the safety net. States can streamline the process for enrolling in child care assistance and other work supports. They also can boost the prospects of poor children by raising the amount of temporary cash assistance available to the neediest families, improving access to food stamps, and helping low-income families afford to rent a home in neighborhoods near good jobs.

- Spend less on prisons, more on schools.In recent decades, states imposed extremely harsh corrections policies that greatly increased both the number of prisoners and their average sentence, at great cost to state budgets. By making these policies more rational, states could shift funding from prison to more productive investments, without harming public safety.

- Improve school funding formulas. K-12 schools in low-income neighborhoods are often poorly funded because the local property tax base is so weak. As a result, children from these neighborhoods begin their education without the resources and supports they need to succeed. States can help by adopting funding formulas that give extra support to low-income districts. Many state funding formulas don’t push back very much against these inequities; some even worsen them.

- Expand early education.States can help families work and kids learn by investing in quality, affordable early care and education programs, as well as after-school programs.

Valerie Wilson: Top 10 Ways to Address Income Inequality

(Author’s note: Given that the primary source of income for most Americans is the pay they receive from their jobs, wages seem like a logical place to start addressing inequality. These ideas are drawn from EPI’s Agenda to Raise America’s Pay.)

- Raise the minimum wage: Raising the minimum wage to $12 by 2020 would benefit about a third of the workforce directly and indirectly.

- Update overtime rules: Moving the overtime threshold to the value it held in 1975—roughly $51,000 today—would provide overtime protections to 6.1 million workers and provide those workers with higher pay.

- Strengthen and protect workers: Strengthen collective bargaining rights to help give workers the leverage they need to bargain for better wages and benefits and to set high labor standards for all workers, and support strong enforcement of labor standards to protect workers.

- Regularize undocumented workers to lift not only their wages but also the wages of all workers in the same fields of work.

- Provide earned sick leave and paid family leave, which would not only raise workers’ pay but also give them more economic security.

- End discriminatory practices that contribute to race and gender inequalities through consistently strong enforcement of antidiscrimination laws in the hiring, promotion, and pay of women and minority workers.

- Prioritize very low rates of unemployment when making monetary policy: Policymakers should not seek to slow the economy until growth of nominal wages is running comfortably above 3.5 percent.

- Create jobs through targeted employment programs and public investments in infrastructure.

- Reduce our trade deficit by stopping destructive currency manipulation.

- Use the tax code to restrain top 1 percent incomes.